Our Standard Operational Procedure (SOP)

This SOP refers to the area of Simon’s Town only, to regulate our pilot project on the Simonsberg Troop of Chacma Baboons

Our approach aims to integrate science, ethics, compassion, an eco-centric vision, human accountability, and principles of restorative justice in order to achieve the regeneration ofNature.

This involves incorporating into our procedures, principles that promote the well-being, safety, and respect for members of our community, of life, and the environment.

Our Principles:

1. We are a community-supported initiative and promote collaboration among residents.

2. While we acknowledge and respect human interests and needs, we promote the recognition of animal sentience and intrinsic worth.

3. We recognise that Nature is an interconnected whole, with relationships between entities and ecosystems that can be affected by human actions.

4. We adopt a multidisciplinary approach that combines insights from climate science, sociology, ethics, ecology, anthropology, behavioural ecology, and Indigenous knowledge to inform our evidence-based advocacy for science-driven policies. We acknowledge the importance of diverse perspectives in tackling complex issues.

5. We acknowledge that wild animals flourish in their natural habitats, and often face harm when they venture into human-dominated landscapes. Meanwhile, we recognise that human expansion has encroached upon, and fragmented ancestral wildlife territories, making encounters unavoidable.

6. To strike a balance, we support, in the case of baboons, that they should not “live in town” while we educate residents on effective strategies to safeguard their legitimate interests and properties when baboons occasionally use urban corridors.

7. Consistent with the provisions of NEM:BA, we aim to create the circumstances for the flourishing of Chacma baboon’s well-being in the natural landscape. In this instance, we look at baboons’ health, overall safety in all areas, and well-being throughout the work of our monitors. At the same time, we prevent and minimise conflict with, harm to, and distress of animals and wildlife.

8. We promote transparency and accountability while building constructive engagement with authorities and monitoring governmental best practices.

9. We respect Indigenous and community values while instilling positive change for biodiversity recovery

10. We strive for continuous improvement and review of our methods to ensure progress.

The Baboon Monitoring and the Civil Coexistence Project

We build on the lessons learned in fifteen years of baboon management from different authorities and service providers under the guidance of a close circle of scientists. A consistent theme in their key recommendations over the years is the urgent need for a comprehensive, solution-focused approach and stringent enforcement of by-laws to eliminate attractants, particularly human waste, that draw baboons into urban areas. However, management has often devolved into a simplistic baboon penalisation system and exclusion strategy, relying on disruptive, violent, crude, and lethal methods. These tactics have polarised the community and failed to address the root issues while being blatantly inconsistent with NEM:BA’s provisions for animal well-being.

It’s time to flip the narrative: baboons are self-determined. They are seeking a safe habitat and essential resources to survive, yet human activities are consistently destroying their environmentand disturbing them, even in their natural habitat. A more compassionate and ecological approach is overdue. We indeed recognise the value of:

1. Restored, maintained, and functioning natural habitats where baboons are not continuously disturbed, harassed, and threatened.

2. Crucial baboon-friendly corridors, to enable them to navigate as safely as possible and access natural resources and areas.

3. Overall protection and comprehensive, integrated approach to safeguarding baboons in those areas.

Via the work of our monitors we:

a. Aim at reversing the effects of habituation. Unlike habituation, which makes baboons dependent on human-derived foods, our monitors focus on rehabilitating them to seek natural food sources, undoing the damage caused by irresponsible or well-meaning but misguided individuals who have fed or inadvertently attracted them with poorly managed waste.

b. Non-intrusively encourage baboons to remain in natural areas and to utilise safe corridors for foraging, while moving cohesively and calmly.

c. Minimise risks to human safety and property while protecting baboons from harm and persecution.

d. Foster a harmonious, safe, legal relationship between humans and baboons, promoting mutual respect and understanding.

Our Objectives:

1. Implementing effective waste management strategies to reduce attractants

2. Employment of local monitors who are trained and constantly upskilled

3. Monitoring of the troop and reporting of any concerns or issues

4. Collection of data on human and animal behaviour

5. Monitoring and reporting of any inappropriate waste disposal or other offenses

6. Collection of data on baboon movement patterns and health

7. Providing support and advice on the best strategies if baboons enter properties

8. Increasing collaboration between local stakeholders on baboon-related matters

9. Promoting the restoration and safety of natural areas

10. Educating residents and visitors about baboon behaviour and conservation

SOP for the Implementation of NEM:BA and the Notion of Animal Well-being

NEM:BA defines well-being as the “holistic circumstances and conditions of an animal, which are conducive to its physical, physiological and mental health and quality of life, including the ability to cope with its environment”. Section 2.a of NEM:BA provides that “all procedural activities that constitute biodiversity management, conservation and sustainable use of wild animals, must consider the well-being of animals”.

We are actively engaging with leading organisations and entities focussed on wildlife well-being to ensure the prompt implementation of these crucial provisions, which have been so far, generally overlooked. Our goal is to collaborate with relevant authorities and stakeholders to make animal and human well-being a central consideration in our conservation efforts.

Our Baboon Monitoring and Civil Co-existence Project is pioneering a legally compliant approach, aligned with NEM:BA, to set a new standard for responsible and effective baboon management in practice.

Our criteria for evaluating the Simonsberg Troop’s well-being are:

1. General safety

2. General body condition

3. Health status (disease, injury, parasite load)

4. Nutrition (access to a variety of healthy food)

5. Access to water quality

6. Shelter from weather

7. Safe resting and roosting places

8. Mortality rates

9. Disease, injury

10. Birth and infant survival rates

Behavioural Well-being:

1. Social structure and cohesion, supportive behaviours

2. Stress levels (aggression, fear, anxiety)

3. Behavioural diversity (foraging, exploring, playing)

4. Social interaction (grooming, affiliative behaviour)

5. Communication (vocalisations, facial expressions)

Environmental Well-being:

1. Habitat quality (vegetation, terrain, climate, post-fire environments, access to corridors)

2. Exposure to human disturbance and threats (traffic, violence, noise, pollution, habitat fragmentation)

3. Safety

Psychological Well–being:

1. Mental stimulation (problem-solving, learning)

2. Emotional state (contentment, relaxation)

3. Sense of control and agency

4. Social support and bonding, caring and waiting for the slowest member of the troop

5. Absence of fear and anxiety

6. Grooming behaviour (Changes in grooming behaviour, such as excessive grooming or lack of grooming, can indicate stress, anxiety, or social issues)

7. Resilience (Baboons who recover quickly from occasional injuries typically have stronger immune systems and better overall health). We look at:

a. Wound healing: this indicates good nutrition, adequate hydration, and effective immune function.

b. Infection resistance

c. Ability to cope with pain and discomfort can indicate emotional resilience and adaptability.

d. Quick recovery of mobility and function after an injury can indicate strong physical health and adaptability.

e. Baboons that receive adequate social support and care from their troop may recover faster and more effectively from injuries. The correct social dynamic reflects a functional healthy troop.

8. Emotional trauma and emotional resilience (The troop’s ability to cope with the emotional impact, for example, of losing juveniles can indicate their emotional resilience and ability to manage stress). Positive indicators of well-being are:

a. Social cohesion and the troop’s ability to maintain social bonds and cohesion after the loss of juveniles. This indicates their strong social support network.

b. Reproductive resilience

c. Maternal care: we observe if the troop has the ability to provide adequate maternal care and support to remaining juveniles.

9. Excessive, non-playful fighting and aggressive behaviour.

This can be an indicator of poor well-being and stress.

While some level of aggression and conflict is normal, we see excessive fighting as a sign of underlying issues affecting baboons’ well-being.

In our experience, this is typically linked to:

a. Imminent threats, including human threat: based on our observations, baboons exhibit signs of stress and distress when shunted by people (including residents, business owners, and service providers) using violent methods such as catapults, pellet guns, and paintball guns. These aggressive tactics can cause significant anxiety and trauma for the animals.

b. Food scarcity and resource competition

c. Social instability and changes in group dynamics, including dominance hierarchies being upset by humans

d. Health issues such as pain, discomfort, or underlying medical conditions can cause irritability and lead to increased aggression.

Physical well-being

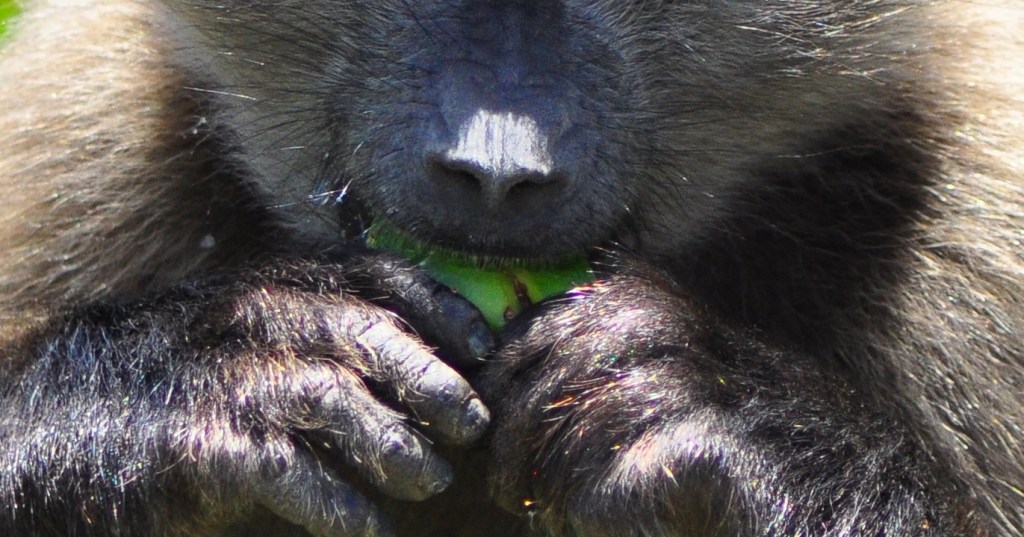

Observation and hands-off monitoring of the quality and appearance of their fur

1. Shine and lustre: we look at shiny, well-groomed fur, while dull or matted fur can indicate poor nutrition, illness, or, most importantly, stress.

2. Length and thickness: baboons with adequate health and well-being typically have longer, thicker fur, while malnourished or stressed individuals may have shorter, thinner fur.

3. Matting and tangling: Excessive matting or tangling can indicate neglect of grooming, which can be a sign of stress, anxiety, or social issues.

4. Parasites and infestations: ticks, fleas, or lice can indicate poor health, poor grooming, or environmental stressors.

5. Colour and pigmentation: Changes in fur colour or pigmentation can indicate nutritional deficiencies, hormonal imbalances, or exposure to environmental toxins.

6. Patchiness or baldness: Patchy or bald areas can indicate skin infections, parasites and fungi, injuries, nutritional deficiencies, hormone imbalances, and stress.

Contraception for aged and/or disabled females

We propose that a study should be conducted to investigate the effects of contraception specifically for elderly or disabled female baboons. Our observations suggest that aged or disabled females face significant challenges during pregnancy and childbirth, often resulting in bodily injuries, arthritis, and high infant mortality rates. While we acknowledge that contraception may impact social dynamics, we hypothesise that this effect would be minimal, particularly for older females within a troop, who may have already established their social standing and reproductive history.

Disabled female baboons face unique challenges that can be exacerbated by pregnancy and childbirth, resulting in aggravating existing disabilities, complications during pregnancy and birth, and increased dependence on the troop, potentially endangering it.

This study would inform evidence-based strategies for improving the health and well-being of elderly and disabled female baboons and their troop.

Grieving of Infants

The forced removal of a dead infant baboon can prolong or intensify the mother’s (and father’s) grieving process and disrupt the troop’s dynamics. Like many primates, baboons exhibit complex emotional behaviours, including grief and mourning.

Scientific documentation of infant corpse-carrying behaviour in primates dates back to the early 20th century, with one of the earliest accounts published in the Journal of Animal Behaviour in 1915. These observations highlight that primates may carry their deceased infants for weeks and show significant distress if humans remove the corpse prematurely.

Both male and female baboons have been observed carrying deceased infants, grooming them, and cleaning their mouths in apparent responses to the loss. Some primates even use tools to clean the bodies of their deceased offspring, demonstrating an awareness of death and engagement in grief-related rituals. Researchers argue that post-mortem care, including grooming, plays an important role in primates’ mourning processes, ending only when the corpse is ultimately abandoned.

Fathers of deceased infants may also exhibit protective behaviours, preventing others from approaching the body. These observations underline the emotional complexity of baboon social structures and the distress caused by the premature removal of a dead infant. Stress in such cases manifests through vocalisations, pacing, and heightened agitation.

For this reason, it is critical to avoid hastily removing deceased infants from baboon troops. If a body obstructs an area, it can be relocated nearby but should remain accessible to the troop.

When deceased infants are removed prematurely, troops have been observed repeatedly returning to the site, searching for the body for weeks. This behaviour can increase the risk of baboons congregating in unsafe areas, further compounding stress for the troop, and possibly exacerbating conflict with the humans who reside in the area.

The National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEM:BA) compels any authority tasked with managing baboon populations, to adopt practices that consider the well-being of these animals. Deceased infants should be left with the troop, so that they can take the body to wild spaces, allowing the natural grieving process to unfold. Eventually, the body will be abandoned and left to decompose naturally. This approach minimises distress and avoids unnecessary interference in the baboons’ social and emotional dynamics.